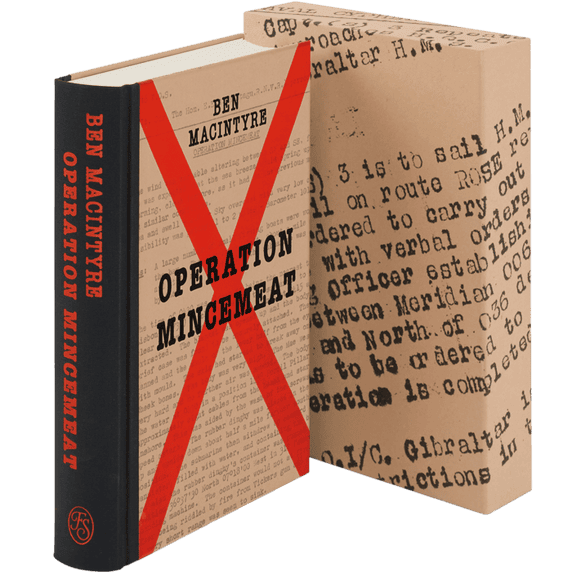

Ben Macintyre’s number-one bestseller Operation Mincemeat is the definitive account of the Second World War’s greatest military deception: a daring hoax that fooled Hitler and changed the course of history.

Illustrated by James Albon

Introduced by Philip Hensher

A modernist masterpiece, Ford Madox Ford’s Great War tetralogy is vividly evoked in this striking two-volume edition.

Chronicling the wartime experiences of Christopher Tietjens, a brilliant government statistician and wealthy landowner, Parade’s End is a portrait of British society during the First World War. Described by Ford as the ‘last English Tory’, Tietjens is torn between his scheming and promiscuous socialite wife, Sylvia, and the progressive Valentine Wannop, a pacifist and suffragette — relationships framed by his reliance on a crumbling moral code. Ford presents a gritty and uncompromising portrait of Tietjens’s life in the trenches of Belgium and France, and his subsequent return home, suffering from crippling shell shock. Through a narrative brimming with modernist experimentation, we follow his struggle to reconcile his relationships while navigating the shifting sands of an evolving social order.

Quarter-bound in cloth with printed paper sides

Set in Photina

1,128 pages in total

Frontispiece and 10 colour illustrations in each volume

Blocked slipcase

The text in this edition follows the definitive Carcanet Press edition

9½˝ x 6¼˝

Ford Madox Ford was one of the most versatile and prolific of the great modernist writers. It is said that he wrote 1,000–2,000 words each day of his life, producing almost 80 books that spanned a variety of genres and often pushed the boundaries of form and style. No other does this more than Parade’s End. This extraordinary four-novel series, published between 1924 and 1928, chronicles the social upheaval wrought by the First World War. But it is equally an exploration of the nature of time, memory and relationships, presented through a deft stream-of-consciousness narrative. At its centre is Christopher Tietjens, a Yorkshireman and ’the last English Tory’, who is transported from the predictable hierarchies of Edwardian Britain to the chaos of the trenches, all the while tormented by his sadistic wife, Sylvia, who Graham Greene described as ’surely the most possessed evil character in the modern novel’. Ford wanted to be ’the historian of his own time’. Here, he achieved his goal, and in doing so produced a series of great experimental novels.

‘There are not many English novels which deserve to be called great: Parade’s End is one of them’

- W. H. Auden

Ford’s prose is brimming with subtle observations about relationships and a Freudian sense of character rarely displayed by British writers of his time. Adapted by Tom Stoppard in 2012 for an acclaimed BBC/HBO television series, Ford’s second masterpiece, after his 1915 novel The Good Soldier, is undergoing a richly deserved revival. Ford is astonishingly perceptive in his presentation of British society as it evolved during and after the war. Like his protagonist, he was known for his phenomenal memory, and he was exceptionally attuned to the class distinctions of the times in which he lived. He also drew on his wartime experiences; he worked for the War Propaganda Bureau and then enlisted, partly to evade his then-girlfriend, Violet Hunt, whose wrathful nature influenced the character of Sylvia. A shell explosion concussed him during the Battle of the Somme, an experience mirrored by Tietjens’s shell shock. He was eventually invalided back to Britain and began writing Parade’s End while convalescing in France.

Just as compelling as the novel’s decade-spanning landscape is Ford’s portrayal of the pensive, highly intelligent, emotionally reticent Tietjens. Few novels have a principal character whose consciousness is so fully expressed, nor convey with such accomplished, artful confusion the complex interrelation of our inner and outer worlds, and the anxieties, misperceptions and contradictions that beset our relationships.

Some Do Not... opens in England in 1912. Tietjens is a young government statistician, admired for his brilliance but with a personal life teetering on the brink of scandal, thanks to his wife’s promiscuity and his own growing attachment to suffragette Valentine Wannop. No More Parades and A Man Could Stand Up are set largely on the Western Front, where Tietjens has been stationed. He is determined to be with Valentine, but Sylvia’s machinations intensify as she seeks the ruin of the husband she desires and loathes in equal measure. The Last Post draws the tetralogy to a bold and poignant close, occupying just a few hours of a summer’s day after the war. Ford moves between the thoughts of multiple characters, offering a fascinating, splintered view both of the protagonist and the post-war era.

‘Virtually alone of the male writing of the 1920s in affirming the ascendance of women and advocating a course of graceful withdrawal from dominance for men’

- David Ayers

This two-volume edition unites Parade’s End with the work of award-winning illustrator James Albon. His reduction lino print illustrations were created through a process he describes as ’so much more physical than drawing, making wildly different marks, and because nothing that has been cut out can be stuck back on, there is virtually no opportunity to correct any mistakes’. For each image, he created dozens of developmental sketches before carving a lino block, rolling it in a layer of ink and feeding it through a printing press. The results are bold and distinctive, with a wonderful sense of character, from the ‘lumpish’ Tietjens to the elegantly wicked Sylvia. They also capture brilliantly the orderliness of their pre-war world, and the volatility of the trenches.

Ford Madox Ford was born Ford Hermann Hueffer in Merton, Surrey, in 1873, the grandson of the artist Ford Madox Brown. In 1908 he founded the English Review, a literary magazine. A prolific novelist, poet, editor and critic, Ford’s novels include Romance (a 1903 collaboration with Joseph Conrad) and The Good Soldier, published in 1915. In that same year Ford enlisted in the army, where he served as an infantry officer. His experiences during the First World War would inspire Parade’s End, published in four parts between 1924 and 1928. After recuperating in the Sussex countryside following the war, Ford moved to Paris, where he launched a second influential literary magazine, The Transatlantic Review. After spending the latter years of his life teaching in the United States, Ford died in Deauville, France, in 1939.

Philip Hensher was born in London in 1965, and educated at Oxford and Cambridge. His books are Other Lulus (1994); Kitchen Venom (1996), which won the Somerset Maugham Award; Pleasured (1998), a short story collection; The Bedroom of the Mister’s Wife (1999); The Mulberry Empire (2002); The Fit (2005); The Northern Clemency (2008), which was shortlisted for the 2008 Man Booker Prize; King of the Badgers (2011); and Scenes from Early Life (2012), which won the Ondaatje Prize. He is a regular contributor to the Spectator, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Bath Spa.

James Albon studied Illustration at Edinburgh College of Art, and went on to a postgraduate scholarship at the Royal Drawing School in London. He received the Gwen May Award from the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers in 2012. He illustrated Parade’s End for The Folio Society in 2013 and The Blue Flower in 2015.