This Folio Life: Joe's blog, no. 39

I recently went down to Dartmoor to interview Alan Lee about his epic illustrations for The Wanderer and other Old English Poems. Widely regarded as a recluse (thanks in large measure to a rather misleading account by Peter Jackson) Alan is in reality a convivial soul (one of his hobbies is tango dancing) and the evening before the interview we had an excellent dinner in a local pub where everyone seemed to know him and greet him cheerily. The interview went well: I had been alerted by the film team that my role was more to prompt Alan than to engage in conversation myself, and that indeed proved to be the case – Alan is very eloquent, as you can see here:

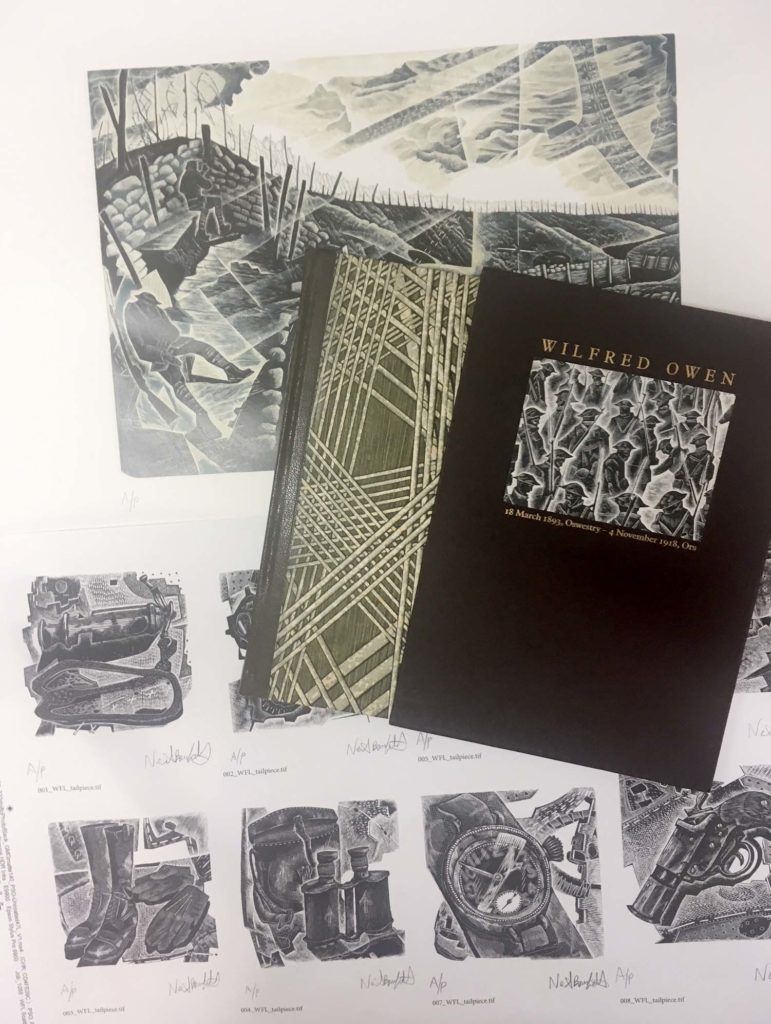

Although I am now semi-detached from Folio, I am still closely involved in some forthcoming limited editions. The next will be a selection of Wilfred Owen’s poems which will be published in November to mark the centenary of his death, just one week before the end of the First World War. The book is loosely in series with our volumes of Rupert Brooke and Edward Thomas, being printed letterpress and bound in quarter leather with paste-paper boards. It is illustrated by Neil Bousfield with colour engravings using the reduction method: this technique involves building up the image with layers of colour, each printing darker than the one before; the colours are all printed from the same block which is cut into more and more at each stage. Here is a photo of one of Neil’s blocks (by this stage cut away for the final printing), and another which shows the binding prototype (probably not the final colours) and proofs of an illustration and some tail-pieces:

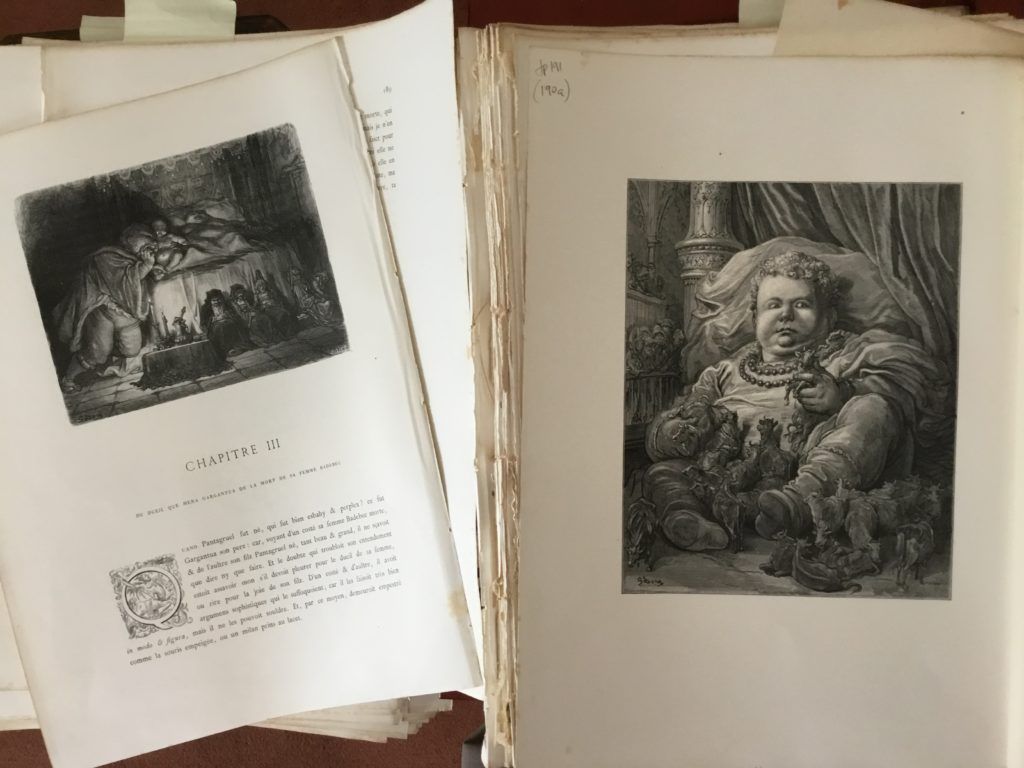

I do most of my designing at home these days, and in the last few weeks my work room here has been submerged by an immense project – Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel with all the 719 illustrations by Gustave Doré. When reproducing an old book like this, we always try and find a damaged (but complete) copy to reproduce from, so as not to spoil a good one; as you can see, we succeeded:

The number of illustrations in the book imposes a severe constraint on the designer, since the flexibility to alter the layout on any given spread is very restricted. Since the translation and the original French differ in length – at times quite markedly – the task is challenging to say the least.

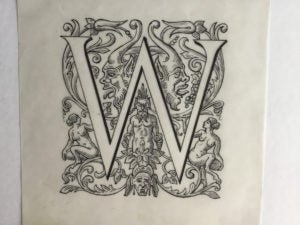

The original French edition of Gargantua has elaborate initial caps at the start of every chapter, but some chapters in the translation start with letters not commonly used by the French notably W, Y and K (is képi the only French word beginning with K, I wonder?). My old comrade-in-arms David Eccles has come to the rescue and filled these gaps with consummate skill. Here is his W, drawn on tracing paper:

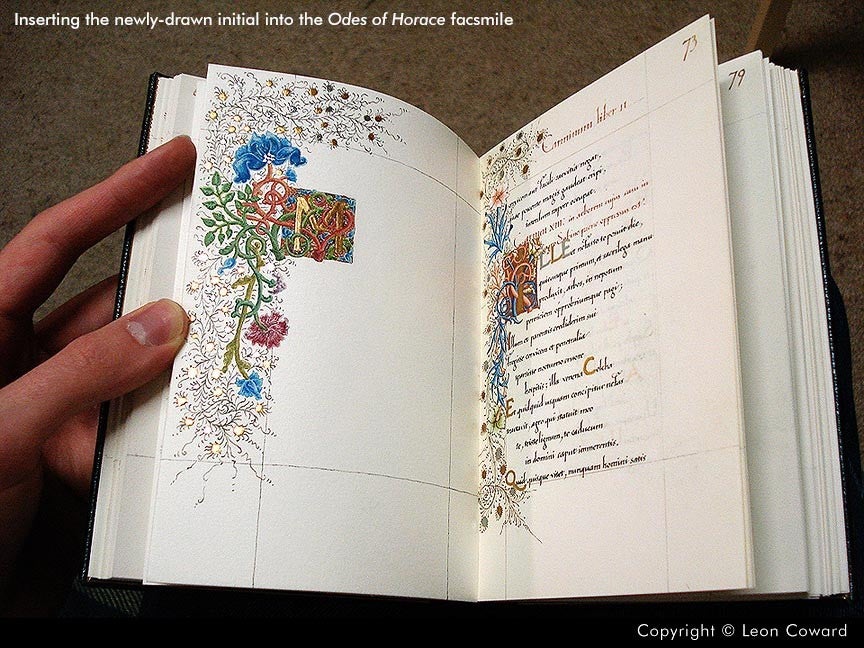

I have been in correspondence for some while with a Folio customer in Australia named Leon Coward, and met him for the first time the other day over a cup of tea at the British Library. A young man in his 20s he was inspired, first by our edition of the Kelmscott Chaucer and later even more so by our facsimile of the Odes of Horace, to make a deep study of the decorative artistry of William Morris. He examined the miniatures very closely to find out how they were done, and then taught himself the techniques employed by Morris – thus enabling him to create his own versions. Even more remarkably, Leon has now worked out the principles underlying Morris’s apparently improvisatory design technique, which enabled him (and now Leon himself) to create new miniatures with extraordinary rapidity – something you would think impossible given their delicate intricacy. In this photo he is holding a copy of our Horace facsimile, into which he has inserted (on the left) his own work – this is not a copy, but an entirely new design in the style of WM.

Finally I can strongly recommend an exhibition at the Brunei Gallery at SOAS in London of photographs by John Thomson taken in Siam and China in the 1860s-70s. Not only did Thomson overcome extraordinary obstacles – cultural and technical – to take these pictures, but he had an ability to make his subjects live which is rare among early photographers (the long exposure times tended to destroy their vitality). Here is a case in point, a Chinese boatwoman:

This blog is by Joe Whitlock Blundell, founder of the limited editions programme at The Folio Society.