The Anglo-Saxons

Still one of the most influential books in its field, Campbell’s account of six hundred years of power struggles, blood-feuds, conquest and gold hoards is now vividly portrayed by Folio with full-colour photographs.

Illustrated by Alan Lee

Introduced by Michael Alexander

Foreword by Bernard O'Donoghue

Translated by Michael Alexander

Limited to 750 copies numbered and signed by Alan Lee

Lavishly ornamented and illustrated by Alan Lee. The Old English texts and their translations by Michael Alexander are set on facing pages for ease of reading.

‘As an illustrator, my aim is not to dictate how things should look, but to serve the author’s vision, and to create an atmosphere, a space between the words where the eye and mind can wander, and imagine for themselves . . . what will happen next.’

- Alan Lee

Alan Lee is the most celebrated living illustrator of myth and fantasy: a recipient of the Kate Greenaway Medal; the Tolkien estate’s artist-of-choice for over 25 years; and an Oscar-winner for his conceptual work on Peter Jackson’s films of The Lord of the Rings. An artist steeped in myth, legend and folklore, his other-worldly images place him at the forefront of a tradition established by the Pre-Raphaelites, Rackham and Dulac.

Lee’s lavish illustrative scheme sets the poems in a modern re-imagining of an illuminated manuscript. Detailed watercolours evoke their magic and their mystery, bringing key moments vividly to life. Intricate ink-drawn ornamental borders – where knot-work turns into writhing dragons and shattered twigs become the broken strings of a harp – mirror their themes of life and death, and the brokenness and integrity of the texts themselves. And witty visual puns, where a picture is simultaneously a pile of twisted branches, bones and hail; the outline of a chicken; and the solution to a riddle, spelled out in runes, reflect their complexity and their humour. Crowning this scheme is the stunning design that adorns the binding – a lightning-shattered evocation of the Sutton Hoo helmet that hints at the inspired, and inspiring, tales enclosed within this magnificent volume.

Translated and introduced by Michael Alexander

Newly commissioned foreword by Bernard O’Donoghue

Set in 15-point Arcadian Bembo and printed on cream wove paper

Eight colour plates by Alan Lee, printed on Art paper and tipped into decorative borders

Numerous other drawings and borders integrated with the text and printed in dove grey

Limitation certificate printed letterpress by The Logan Press on Tintoretto paper, signed and numbered by the artist

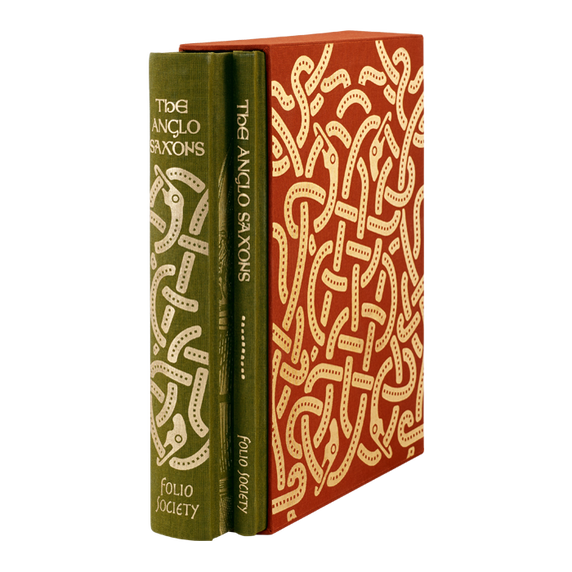

Quarter-bound in goatskin with blind and silver blocking on the spine. Boards printed and blocked with designs by the artist

Endpapers printed with a design by the artist

Top edge gilded in gunmetal foil, ribbon marker

244 pages. Book size: 13¼˝ x 9½˝

Presented in a clothbound slipcase blocked in silver on the front board

Poems

The Ruin

The Wanderer and The Seafarer

Love Poems

The Wife’s Lament

The Husband’s Message

Wulf and Eadwacer

Heroic Poems

Deor

The Fight at Finnsburgh

The Battle of Brunanburgh

The Battle of Maldon

Widsith

Gnomic Verses

The Dream of the Rood

The Exeter Riddles

Over 1000 years ago, the visionary Anglo-Saxon ruler Alfred the Great strived to replace Latin with English as the principal language of his kingdom. Verse in the vernacular flourished and, at the turn of the 11th century, monastic scribes wrote down these innovative oral compositions creating the first literature in English. Just decades later, William the Conqueror’s Norman invasion transformed the linguistic landscape of England so dramatically that, before long, these verses had become the unreadable remnants of an extinct language. One of the greatest collections of Anglo-Saxon poetry – the Exeter Book – was dismissed in an early 14th century inventory as ‘worthless’, and used as a beermat and chopping board, its vellum pages stained, sliced and singed.

After centuries of neglect and ill-treatment, the tattered remains of this Old English literature were finally recovered in the 19th century. The tiny handful of preserved manuscripts were transcribed, edited and translated by pioneering scholars, attracted by their historical value and their heroic and ‘Romantic’ qualities. Since then, these miraculous survivors have been acknowledged as the earliest known masterpieces of English poetry, influencing and inspiring writers as varied as William Morris and Ezra Pound, Alfred Tennyson and J. R. R. Tolkien. Shafts of light illuminating a dark age, they give a unique insight into the Anglo-Saxon world, over-shadowed by Roman ruins and embattled by Viking incursions, torn between pagan fatalism and Christian hope.

No man blessed

with a happy land-life is like to guess

how I, aching-hearted, on ice-cold seas

have wasted whole winters

- From The Seafarer

One of the most striking features of Old English poetry is its directness. Its narrators frequently address us in the first person, sharing deep truths drawn from lived experience, and exploring a remarkable range of subjects and emotions: the loneliness of the exile, cut adrift from his lord, and of the sailor, lured from the comforts of civilisation by the call of the sea; the yearning for a lost Golden Age provoked by an encounter with monumental ruins; and the bitterness of a loyal wife, alienated from her husband by false accusations. Epic accounts of resounding victory in battle and heroic defeat at the hands of marauding invaders sit alongside an ecstatic description of Christ’s crucifixion, narrated by the Cross itself; pithy proverbs and delightfully tantalising riddles follow musings on the fate of the successful – and the unsuccessful – poet.

There’s a vitality to these poems, written as they were at a time when life was so much more embattled, more desperate and fragile

- Bernard O’Donoghue

Michael Alexander first started producing his masterful translations of Old English verse nearly sixty years ago. His anthologies have achieved classic status, winning praise from Ted Hughes, W. H. Auden and Seamus Heaney, and bringing Old English literature to an audience of millions. To match the unique force of the original texts, Alexander’s poetic renderings adhere to the characteristic Old English metre – unrhymed lines with four stressed syllables, linked by a strict pattern of internal alliteration. At the same time, his goal of ‘fidelity’ rather than accuracy allows him to capture the spirit, as well as the meaning of these poems, giving a powerful sense that we are hearing them as if performed aloud for the very first time.

This parallel edition presents the Old English texts and their translations on facing pages, giving lay-readers the flavour of the original language, and scholars the chance to admire Alexander’s skill. It also includes his detailed historical introduction, introductions to the individual poems, scholarly notes, proposed answers to the riddles, suggestions for further reading, a short explanation of runes, and a comprehensive glossary. This highly informative text is complemented by a specially commissioned foreword from Bernard O’Donoghue, winner of the 1995 Whitbread prize for Poetry, who has described the Old English elegies as his ‘model for the perfectly formed lyric poem’.