Discovering Charles Stewart | A lifelong obsession with Uncle Silas

Former Folio Editorial Director Sue Bradbury recalls the life, work and inspiration of Charles Stewart, who illustrated and developed a lifelong obsession with Sheridan Le Fanu's Uncle Silas. Stewart's extraordinary work is now the subject of an acclaimed exhibition at the Royal Academy – Charles Stewart: Black and White Gothic.

In the spring of 1984, The Folio Society mounted its first exhibition of illustration at the Royal Festival Hall. The Society, which was founded just after the war to restore the arts of typography, binding and illustration to commercially produced books, was, by the 1980s, the proud owner of a large collection of originals by artists of the calibre of Edward Bawden, Mervyn Peake, Joan Hassall and Quentin Blake. There were more than enough to furnish an exhibition, but it also seemed to be the perfect opportunity to expand Folio’s stable of illustrators, so other artists were invited to submit work for inclusion.

And along came Charles Stewart: a neat, rounded man with a gentle pink face and snow-white hair, dressed in immaculate tweeds and carrying a plastic bag. The bag contained about 30 exquisitely detailed and wonderfully sinister illustrations for Uncle Silas, a sensational and mysterious novel written in 1864 by Sheridan Le Fanu. We hadn’t come across the book before, but we decided there and then that if the novel was even half as good as the illustrations, we had to publish it.

[caption id="attachment_2562" align="aligncenter" width="403"] Charles Stewart, Uncle Silas: Frontispiece, 1947.[/caption]

Charles’s obsession with Uncle Silas had been born out of his admiration for M. R. James, who had described Le Fanu as ‘one of the best storytellers of the last age’. Trained at the Byam Shaw School of Art, Charles had hoped to work as a theatre designer (he would have made an exceptionally good one), but the war put paid to that idea: as a conscientious objector, he found work as a stretcher-bearer at an ARP (Air Raid Precaution) depot in Battersea, and, in the lulls between raids, took himself off to a suitably gothic tower in the big Victorian house in which they were based, and began his life’s work. When off-duty, much of his time was spent scouring second-hand bookshops in search of illustrated 19th-century books and fashion plates to build up a pictorial reference library of the period. He was a particular fan – predictably – of George Cruikshank and Phiz (Hablot Knight Brown).

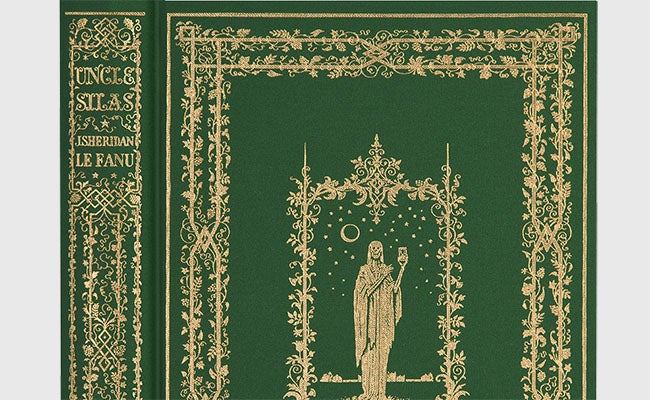

Charles’s aim was to convey the style of the early Victorian artists with pen and ink – an exacting task as Victorian artists mostly used etching or steel-engraving as a means of reproducing their work. His desire to emulate the illustrations of the 1840s (the decade in which the novel was set) proved, he told me, to be his downfall. ‘My penwork,’ he said, ‘known to my friends as my knitting, was so close in texture that it proved impossible to reproduce by the usual line block process.’ The Bodley Head, for whom the illustrations were intended, backed out, and thus it was that The Folio Society came to publish them for the first time nearly 40 years later – with, needless to say, numerous additions and a binding design and title page to out-gothic even the most extreme examples of the genre.

[caption id="attachment_2549" align="aligncenter" width="401"]

Charles Stewart, Uncle Silas: Frontispiece, 1947.[/caption]

Charles’s obsession with Uncle Silas had been born out of his admiration for M. R. James, who had described Le Fanu as ‘one of the best storytellers of the last age’. Trained at the Byam Shaw School of Art, Charles had hoped to work as a theatre designer (he would have made an exceptionally good one), but the war put paid to that idea: as a conscientious objector, he found work as a stretcher-bearer at an ARP (Air Raid Precaution) depot in Battersea, and, in the lulls between raids, took himself off to a suitably gothic tower in the big Victorian house in which they were based, and began his life’s work. When off-duty, much of his time was spent scouring second-hand bookshops in search of illustrated 19th-century books and fashion plates to build up a pictorial reference library of the period. He was a particular fan – predictably – of George Cruikshank and Phiz (Hablot Knight Brown).

Charles’s aim was to convey the style of the early Victorian artists with pen and ink – an exacting task as Victorian artists mostly used etching or steel-engraving as a means of reproducing their work. His desire to emulate the illustrations of the 1840s (the decade in which the novel was set) proved, he told me, to be his downfall. ‘My penwork,’ he said, ‘known to my friends as my knitting, was so close in texture that it proved impossible to reproduce by the usual line block process.’ The Bodley Head, for whom the illustrations were intended, backed out, and thus it was that The Folio Society came to publish them for the first time nearly 40 years later – with, needless to say, numerous additions and a binding design and title page to out-gothic even the most extreme examples of the genre.

[caption id="attachment_2549" align="aligncenter" width="401"] Charles Stewart, 'The figure of Uncle Silas rose up, with a death like scowl', undated.[/caption]

By then Charles was nearly 70. He still walked with the light and upright carriage of the ballet dancer he had once been, though his eyesight was not as keen as it had been, and his additions were drawn to a larger scale than the originals. Given his love of sensational stories and fairy-tales, I was not surprised to discover that there was a ghost story behind the Uncle Silas illustrations. Charles was a meticulous researcher, but for a while he had been foxed by what to use as a reference for Bartram-Haugh, the house in which Maud Ruthyn meets her nemesis. He had poured over copies of Country Life, and had made copious enquiries, but he always came back to Lyme Hall in Cheshire even though it did not quite fit the requirements of the story. Lyme was a fine early 18th-century pile, but descriptions of it did not accommodate the ‘inner court’ so essential to the plot of Uncle Silas. In the end he went with Lyme anyway, and discovered some years later not only that Le Fanu had been a frequent visitor there, but that the core of the house was indeed Tudor, just as he had described it in the book.

His letters to Joe Whitlock Blundell, Folio’s Art Director, and me during the production of Uncle Silas, and the two subsequent books he illustrated for us, Mistress Masham’s Repose and the Ghost Stories, are a delight. Unfailingly courteous, attentive to the events in both our lives, demanding (in the nicest possible way) the highest standards, both from us and from himself, and packed with recondite information, they kept us warmed and entertained until he died in 2001. My only regret is that we were unable to take him up on his suggestion of Sidonia the Sorceress by Wilhelm Meinhold, subtitled ‘The supposed Destroyer of the Whole Reigning Ducal House of Pomerania’. This book, based on the story of ‘a young girl of noble family who, after a life of relentless crime, was burnt as a witch at Stettin in 1620’, became cult reading among the Romantics and the Pre-Raphaelites. It was championed by D. G. Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, and was reprinted in 1893 by William Morris’s Kelmscott Press. I have a feeling we missed a trick.

Among other film stills, theatre designs, proofs and publishing materials, the illustrations for Uncle Silas will be exhibited at Charles Stewart: Black and White Gothic at the Royal Academy of Arts until 15 February. Find out more here.

Other events:

Charles Stewart and the Art of Illustration. Join Sue Bradbury and exhibition director Amanda Doran for a free lunchtime lecture Monday 19 February 1pm–2pm. Click here for more details.

Behind-the-Scenes Library Visit – Monochrome Tomes: A Show and Tell of Black & White Book Illustration. Enjoy rare access to the Royal Academy's Historic Book Collection with an intimate guide through 250 years of black-and-white book illustration. Monday 9 February 2pm–4.30pm. More details here.

Charles Stewart, 'The figure of Uncle Silas rose up, with a death like scowl', undated.[/caption]

By then Charles was nearly 70. He still walked with the light and upright carriage of the ballet dancer he had once been, though his eyesight was not as keen as it had been, and his additions were drawn to a larger scale than the originals. Given his love of sensational stories and fairy-tales, I was not surprised to discover that there was a ghost story behind the Uncle Silas illustrations. Charles was a meticulous researcher, but for a while he had been foxed by what to use as a reference for Bartram-Haugh, the house in which Maud Ruthyn meets her nemesis. He had poured over copies of Country Life, and had made copious enquiries, but he always came back to Lyme Hall in Cheshire even though it did not quite fit the requirements of the story. Lyme was a fine early 18th-century pile, but descriptions of it did not accommodate the ‘inner court’ so essential to the plot of Uncle Silas. In the end he went with Lyme anyway, and discovered some years later not only that Le Fanu had been a frequent visitor there, but that the core of the house was indeed Tudor, just as he had described it in the book.

His letters to Joe Whitlock Blundell, Folio’s Art Director, and me during the production of Uncle Silas, and the two subsequent books he illustrated for us, Mistress Masham’s Repose and the Ghost Stories, are a delight. Unfailingly courteous, attentive to the events in both our lives, demanding (in the nicest possible way) the highest standards, both from us and from himself, and packed with recondite information, they kept us warmed and entertained until he died in 2001. My only regret is that we were unable to take him up on his suggestion of Sidonia the Sorceress by Wilhelm Meinhold, subtitled ‘The supposed Destroyer of the Whole Reigning Ducal House of Pomerania’. This book, based on the story of ‘a young girl of noble family who, after a life of relentless crime, was burnt as a witch at Stettin in 1620’, became cult reading among the Romantics and the Pre-Raphaelites. It was championed by D. G. Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, and was reprinted in 1893 by William Morris’s Kelmscott Press. I have a feeling we missed a trick.

Among other film stills, theatre designs, proofs and publishing materials, the illustrations for Uncle Silas will be exhibited at Charles Stewart: Black and White Gothic at the Royal Academy of Arts until 15 February. Find out more here.

Other events:

Charles Stewart and the Art of Illustration. Join Sue Bradbury and exhibition director Amanda Doran for a free lunchtime lecture Monday 19 February 1pm–2pm. Click here for more details.

Behind-the-Scenes Library Visit – Monochrome Tomes: A Show and Tell of Black & White Book Illustration. Enjoy rare access to the Royal Academy's Historic Book Collection with an intimate guide through 250 years of black-and-white book illustration. Monday 9 February 2pm–4.30pm. More details here.

Charles Stewart, Uncle Silas: Frontispiece, 1947.[/caption]

Charles’s obsession with Uncle Silas had been born out of his admiration for M. R. James, who had described Le Fanu as ‘one of the best storytellers of the last age’. Trained at the Byam Shaw School of Art, Charles had hoped to work as a theatre designer (he would have made an exceptionally good one), but the war put paid to that idea: as a conscientious objector, he found work as a stretcher-bearer at an ARP (Air Raid Precaution) depot in Battersea, and, in the lulls between raids, took himself off to a suitably gothic tower in the big Victorian house in which they were based, and began his life’s work. When off-duty, much of his time was spent scouring second-hand bookshops in search of illustrated 19th-century books and fashion plates to build up a pictorial reference library of the period. He was a particular fan – predictably – of George Cruikshank and Phiz (Hablot Knight Brown).

Charles’s aim was to convey the style of the early Victorian artists with pen and ink – an exacting task as Victorian artists mostly used etching or steel-engraving as a means of reproducing their work. His desire to emulate the illustrations of the 1840s (the decade in which the novel was set) proved, he told me, to be his downfall. ‘My penwork,’ he said, ‘known to my friends as my knitting, was so close in texture that it proved impossible to reproduce by the usual line block process.’ The Bodley Head, for whom the illustrations were intended, backed out, and thus it was that The Folio Society came to publish them for the first time nearly 40 years later – with, needless to say, numerous additions and a binding design and title page to out-gothic even the most extreme examples of the genre.

[caption id="attachment_2549" align="aligncenter" width="401"]

Charles Stewart, Uncle Silas: Frontispiece, 1947.[/caption]

Charles’s obsession with Uncle Silas had been born out of his admiration for M. R. James, who had described Le Fanu as ‘one of the best storytellers of the last age’. Trained at the Byam Shaw School of Art, Charles had hoped to work as a theatre designer (he would have made an exceptionally good one), but the war put paid to that idea: as a conscientious objector, he found work as a stretcher-bearer at an ARP (Air Raid Precaution) depot in Battersea, and, in the lulls between raids, took himself off to a suitably gothic tower in the big Victorian house in which they were based, and began his life’s work. When off-duty, much of his time was spent scouring second-hand bookshops in search of illustrated 19th-century books and fashion plates to build up a pictorial reference library of the period. He was a particular fan – predictably – of George Cruikshank and Phiz (Hablot Knight Brown).

Charles’s aim was to convey the style of the early Victorian artists with pen and ink – an exacting task as Victorian artists mostly used etching or steel-engraving as a means of reproducing their work. His desire to emulate the illustrations of the 1840s (the decade in which the novel was set) proved, he told me, to be his downfall. ‘My penwork,’ he said, ‘known to my friends as my knitting, was so close in texture that it proved impossible to reproduce by the usual line block process.’ The Bodley Head, for whom the illustrations were intended, backed out, and thus it was that The Folio Society came to publish them for the first time nearly 40 years later – with, needless to say, numerous additions and a binding design and title page to out-gothic even the most extreme examples of the genre.

[caption id="attachment_2549" align="aligncenter" width="401"] Charles Stewart, 'The figure of Uncle Silas rose up, with a death like scowl', undated.[/caption]

By then Charles was nearly 70. He still walked with the light and upright carriage of the ballet dancer he had once been, though his eyesight was not as keen as it had been, and his additions were drawn to a larger scale than the originals. Given his love of sensational stories and fairy-tales, I was not surprised to discover that there was a ghost story behind the Uncle Silas illustrations. Charles was a meticulous researcher, but for a while he had been foxed by what to use as a reference for Bartram-Haugh, the house in which Maud Ruthyn meets her nemesis. He had poured over copies of Country Life, and had made copious enquiries, but he always came back to Lyme Hall in Cheshire even though it did not quite fit the requirements of the story. Lyme was a fine early 18th-century pile, but descriptions of it did not accommodate the ‘inner court’ so essential to the plot of Uncle Silas. In the end he went with Lyme anyway, and discovered some years later not only that Le Fanu had been a frequent visitor there, but that the core of the house was indeed Tudor, just as he had described it in the book.

His letters to Joe Whitlock Blundell, Folio’s Art Director, and me during the production of Uncle Silas, and the two subsequent books he illustrated for us, Mistress Masham’s Repose and the Ghost Stories, are a delight. Unfailingly courteous, attentive to the events in both our lives, demanding (in the nicest possible way) the highest standards, both from us and from himself, and packed with recondite information, they kept us warmed and entertained until he died in 2001. My only regret is that we were unable to take him up on his suggestion of Sidonia the Sorceress by Wilhelm Meinhold, subtitled ‘The supposed Destroyer of the Whole Reigning Ducal House of Pomerania’. This book, based on the story of ‘a young girl of noble family who, after a life of relentless crime, was burnt as a witch at Stettin in 1620’, became cult reading among the Romantics and the Pre-Raphaelites. It was championed by D. G. Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, and was reprinted in 1893 by William Morris’s Kelmscott Press. I have a feeling we missed a trick.

Among other film stills, theatre designs, proofs and publishing materials, the illustrations for Uncle Silas will be exhibited at Charles Stewart: Black and White Gothic at the Royal Academy of Arts until 15 February. Find out more here.

Other events:

Charles Stewart and the Art of Illustration. Join Sue Bradbury and exhibition director Amanda Doran for a free lunchtime lecture Monday 19 February 1pm–2pm. Click here for more details.

Behind-the-Scenes Library Visit – Monochrome Tomes: A Show and Tell of Black & White Book Illustration. Enjoy rare access to the Royal Academy's Historic Book Collection with an intimate guide through 250 years of black-and-white book illustration. Monday 9 February 2pm–4.30pm. More details here.

Charles Stewart, 'The figure of Uncle Silas rose up, with a death like scowl', undated.[/caption]

By then Charles was nearly 70. He still walked with the light and upright carriage of the ballet dancer he had once been, though his eyesight was not as keen as it had been, and his additions were drawn to a larger scale than the originals. Given his love of sensational stories and fairy-tales, I was not surprised to discover that there was a ghost story behind the Uncle Silas illustrations. Charles was a meticulous researcher, but for a while he had been foxed by what to use as a reference for Bartram-Haugh, the house in which Maud Ruthyn meets her nemesis. He had poured over copies of Country Life, and had made copious enquiries, but he always came back to Lyme Hall in Cheshire even though it did not quite fit the requirements of the story. Lyme was a fine early 18th-century pile, but descriptions of it did not accommodate the ‘inner court’ so essential to the plot of Uncle Silas. In the end he went with Lyme anyway, and discovered some years later not only that Le Fanu had been a frequent visitor there, but that the core of the house was indeed Tudor, just as he had described it in the book.

His letters to Joe Whitlock Blundell, Folio’s Art Director, and me during the production of Uncle Silas, and the two subsequent books he illustrated for us, Mistress Masham’s Repose and the Ghost Stories, are a delight. Unfailingly courteous, attentive to the events in both our lives, demanding (in the nicest possible way) the highest standards, both from us and from himself, and packed with recondite information, they kept us warmed and entertained until he died in 2001. My only regret is that we were unable to take him up on his suggestion of Sidonia the Sorceress by Wilhelm Meinhold, subtitled ‘The supposed Destroyer of the Whole Reigning Ducal House of Pomerania’. This book, based on the story of ‘a young girl of noble family who, after a life of relentless crime, was burnt as a witch at Stettin in 1620’, became cult reading among the Romantics and the Pre-Raphaelites. It was championed by D. G. Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, and was reprinted in 1893 by William Morris’s Kelmscott Press. I have a feeling we missed a trick.

Among other film stills, theatre designs, proofs and publishing materials, the illustrations for Uncle Silas will be exhibited at Charles Stewart: Black and White Gothic at the Royal Academy of Arts until 15 February. Find out more here.

Other events:

Charles Stewart and the Art of Illustration. Join Sue Bradbury and exhibition director Amanda Doran for a free lunchtime lecture Monday 19 February 1pm–2pm. Click here for more details.

Behind-the-Scenes Library Visit – Monochrome Tomes: A Show and Tell of Black & White Book Illustration. Enjoy rare access to the Royal Academy's Historic Book Collection with an intimate guide through 250 years of black-and-white book illustration. Monday 9 February 2pm–4.30pm. More details here.