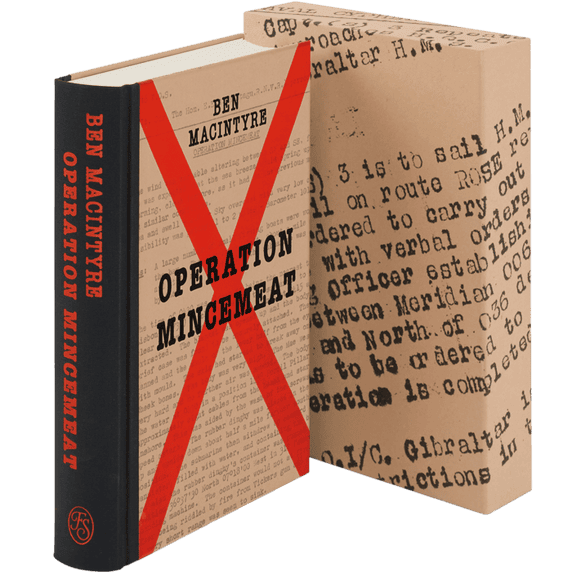

Ben Macintyre’s number-one bestseller Operation Mincemeat is the definitive account of the Second World War’s greatest military deception: a daring hoax that fooled Hitler and changed the course of history.

Introduced by Hew Strachan

Translated by Robin Buss

A hauntingly illustrated edition of Under Fire, Henri Barbusse’s uniquely devastating anti-war masterpiece published at the height of the First World War.

This war is about appalling, superhuman exhaustion, about water up to your belly and about mud, dung and repulsive filth. It is about moulding faces and shredded flesh and corpses that do not even look like corpses any more...

A searing evocation of the squalid conditions and the physical and psychological horrors endured by soldiers fighting on the Western Front, Under Fire is the French novel of the First World War. Astonishingly, it was published in 1916, at the very height of the conflict.

Henri Barbusse started Under Fire in hospital after being invalided out from the front-line, drawing on the journal he kept in the trenches. In a series of meticulously observed episodes, we follow a fictionalised squad – a diverse group of men of all ages, and from all over France – as they come out of the front-line and rest, return to combat, endure a nightmarish bombardment, participate in a chaotic assault on a German trench and then face up to its appalling aftermath. Much of Under Fire is written in the present tense, making us virtual eyewitnesses, and its graphic descriptions of forced marches through excrement, horrific injuries and putrefying corpses established Barbusse as ‘the Zola of the trenches’.

Appearing initially in installments in the literary magazine L’Œuvre to avoid censorship, Under Fire was devoured by readers on the battlefield and at home, desperate for an ‘authentic’ account of the war. Within a year it had sold almost a quarter of a million copies, and was awarded the Prix Goncourt, France’s most prestigious literary prize, before it had even been published in book-form. Ironically, its potential to demoralise was only recognised in Austria and Germany, where it was banned.

If you get the squaddies in your book to speak, will you make them speak like they really do, or will you tidy it up and make it proper? … I’ll put the swearwords in, because it’s the truth.

Barbusse was determined that Under Fire would present an unvarnished portrait of the rank-and-file French soldier – the poilu – from his ragged appearance to his coarse language. Controversially, he also described the anger that soldiers felt towards those living comfortably at home, and the shame produced by their own nightmarish experiences. Under Fire is dedicated to the memory of his fallen comrades – between 9 and 13 January 1915 half of his unit was killed – and Barbusse used his royalties to found the Association Républicaine des Anciens Combattants, an organisation devoted to defending the rights, and the testimony, of war veterans.

Robin Buss’s translation captures perfectly Barbusse’s extraordinary combination of the crude, the poetic and the apocalyptic. This stunning edition enhances his vivid text with haunting documentary photographs of ordinary French soldiers taken on the battlefield itself and an introduction by pre-eminent military historian, Hew Strachan, exploring Under Fire’s groundbreaking and controversial combination of fact and fiction.

Bound in printed and blocked cloth

Set in Galliard with Folio display

376 pages

Frontispiece, 16 black & white integrated photographs

Printed endpapers

Plain slipcase

9½˝ x 6¼˝

Henri Barbusse was born in the outskirts of Paris, at Asnières-sur-Seine, in 1873. He became a member of the Paris literary milieu at a young age and published his first collection of poems, Pleureuses, in 1895, and his first novel, L’Enfer, in 1908. At the outbreak of the First World War, despite being 41 years old, in poor health and a pre-war pacifist, Barbusse enlisted with the French Army and served for 17 months in a front-line unit before being moved to a clerical position following pulmonary damage caused by an explosion. His account of the war, Le Feu (trans. Under Fire) was published in 1916 and won the Prix Goncourt in the same year. In 1917 he was co-founder and first president of the Republican Association of Veterans (ARAC). Following the war he worked as a newspaper editor and founded the pacifist movement Clarity. In 1923 he joined the French Communist Party and travelled extensively in the USSR, where he died in 1935.

Robin Buss (1939–2006) was a British journalist, translator, and critic for film and television. He studied at the University of Paris where he took a degree and doctorate in French literature, and later published critical studies of works by Vigny and Cocteau. He was the co-author of the Encyclopaedia Britannica entry on ‘French Literature’, and wrote three books on European cinema, The French Through Their Films (1988), Italian Films (1989) and French Film Noir (1994). Fluent in several languages but predominantly a Francophile, he translated works by Balzac, Dumas, Sartre and Zola, amongst others.

Hew Strachan was formerly the Chichele Professor of the History of War at Oxford University, and since 2015 has been Professor of International Relations at the University of St Andrews. He is a member of the Strategic Advisory Panel of the Chief of the Defence Staff, the Defence Academy Advisory Board and the Council of the International Institute for Strategic Studies. He is a Trustee of the Imperial War Museum and a Commonwealth War Graves Commissioner, and serves on the National Committee for the Centenary of the First World War. His books include The First World War: Volume 1: To Arms (2001), The First World War: An Illustrated History (2003), Clausewitz’s On War: A Biography (2007) and The Direction of War (2013); he is also the editor of The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War (2014 edition). A Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Strachan was knighted in 2013.