This Folio Life: Celebrating 60 years of James and the Giant Peach

How did Roald Dahl become Roald Dahl? Biographer and Chair of Trustees of Roald Dahl’s Marvellous Children’s Charity, Donald Sturrock, uncovers the creative journey behind James and the Giant Peach and how an unlikely suggestion by Dahl’s agent changed his life’s path forever.

James and the Giant Peach was Roald Dahl’s first children’s book. While writing it, he took his first steps away from being an adult short-story writer and set off into the unknown territory of juvenile fiction. By the time he died, thirty years later, he would be regarded as the pre-eminent children’s writer of his day. But his journey to that end was one he embarked upon with such reluctance that he nearly missed his appointment with destiny altogether.

It was the autumn of 1959 and Roald was suffering from writer’s block. He had recently submitted his third story collection, Kiss Kiss, to Alfred Knopf, his publisher. It had taken him six years to write. When Knopf read it, he thought his author was going off the rails. The new tales were too gruesome for his taste and he told Roald that he was considering dropping the book from his autumn list. Roald wrote gloomily to his agent, Sheila St Lawrence, and told her he had run out of ideas. Positive as ever, Sheila suggested he try his hand at writing for children. ‘I think you could come up with a book with tremendous appeal to both adults and children,’ she enthused. ‘Here is the chance for you to get away from the short story formula, which is imprisoning you at the moment, and re-indulge yourself in the realm of fantasy writing at which you are so very good.’

Roald hesitated before taking her bait. He was forty-three and had spent nearly twenty years trying to build a career as an adult writer. He was married to the American actress Patricia Neal, whose career was thriving. She was often away from home, so Roald was largely responsible for looking after their young family and consequently struggled to find time to write. He had, however, begun inventing bedtime stories for his two young daughters, Olivia and Tessa. ‘Now and again I managed to hit on something that caused a spark of excitement in their eyes,’ he told a convention of librarians many years later, ‘and when that happened, they would always say on the following evening “tell us some more.”’

So he jotted down a few of the ideas that had tickled his daughters’ fancy. One of them was about a cherry that would not stop growing. But he did not know what to do with it. He wanted to write about animals, too, but felt that Beatrix Potter had slightly cramped his ability to do anything original there. ‘There seemed to be jolly little that had not been written about,’ he told me years later, ‘except maybe little things like earthworms and centipedes and spiders.’ So he started to make notes about them, too. Then, on a family holiday in Norway, the two ideas came together. The cherry became a peach and the story acquired a protagonist: James Henry Trotter.

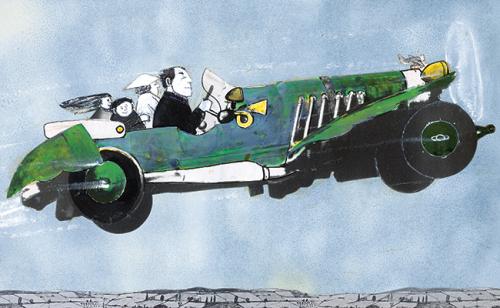

James would become typical of Roald’s young heroes: an orphan, who is lonely and under-appreciated, but also brave, good-hearted and inventive. They will find friendship not among children of their own age, but with maverick characters, who appear unsettling at first, even frightening – a madcap chocolate-making genius, a giant or, in James’s case, a gang of outsize bugs, including a centipede, a spider, an earthworm and a ladybird.

By the spring of 1960, the story was in its second revision. Roald showed it to Sheila, who could not contain her own enthusiasm. ‘Really, honestly, truly,’ she responded, ‘I think you’ve done the undoable, and crossed the border between adult and juvenile.’ He had.

The path to becoming a classic however, would not be an easy one. While the book sold well in the USA, both James and the Giant Peach and Roald’s next book, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, struggled to find a publisher in the UK. Children’s fiction editors found both books too raucous, subversive, vulgar and edgy. Discombobulated by their novelty, all the main publishing houses repeatedly turned them down. Eventually, after six years, Roald turned to a neighbour, Rayner Unwin, essentially an academic publisher, but one whose father Stanley had published Lord of the Rings when others had passed on it. Unwin agreed to publish the book and split all profits fifty-fifty if Roald covered half the printing costs.

The rest is history. From the moment of its first UK publication in 1967, children embraced it as a transformative story of friendship, adventure and triumph over adversity. Adults quickly followed suit. Since then, it has touched the heart of millions of children around the world with its wit, humour and distinctive magic. A tale that began life as a reluctant bed-time narrative for two young girls has since become one of the best-loved classics of the genre.