How We See Frankenstein’s Creature

From its birth in the imagination of Mary Shelley, Frankenstein’s creature has taken on a life of its own as one of popular culture’s most potent images. Miranda Seymour, Mary Shelley’s biographer and the introducer of an earlier edition of Frankenstein (now no longer in print but replaced by a new Folio Collectable edition), considers the making and meanings of a visual icon.

[caption id="attachment_3642" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Frankenstein's Monster: Boris Karloff; Glenn Strange; Lon Chaney[/caption]

The novel, brought out by the London firm of Lackington in 1818, was initially unillustrated. In 1831, when Richard Bentley acquired the copyright from Mary Shelley for £60, he commissioned an artist of modest fame, Thomas Holst, to provide a title-page illustration and a frontispiece showing the monster at the time of his laboratory birth. It is reasonable to assume that Mary Shelley saw and approved these plates.

Holst’s original title page shows Victor Frankenstein saying goodbye to his beloved Elizabeth as he sets off for Ingolstadt, where he is to study the sciences. Elizabeth Lavenza is the perfect young lady, ringletted and demure, with a crucifix strung over a chest as flat as a boy’s; Victor, in skirted tunic and an equally copious set of curls, looks away from her, his thoughts already fixed on the future.

The representation of Frankenstein’s laboratory at the moment that the monster wakes into life is more interesting. In later editions, it took the place of the title page. Atmospherically, the scene belongs to one of the gothic extravaganzas written by Percy Bysshe Shelley during his schooldays. The moon glares through an ancient window more appropriate to a Norman church than a student’s laboratory; magic runes hang on the wall; bones litter the floor. Straight haired and hollow-cheeked, the creature who stretches across the foreground of Holst’s arresting plate looks like Caliban on steroids. He has a gaunt beauty; you would never question the fact that he is human rather than the ‘daemon’ described by his maker, here seen taking a hasty departure from the birth chamber.

[caption id="attachment_3638" align="aligncenter" width="544"]

Frankenstein's Monster: Boris Karloff; Glenn Strange; Lon Chaney[/caption]

The novel, brought out by the London firm of Lackington in 1818, was initially unillustrated. In 1831, when Richard Bentley acquired the copyright from Mary Shelley for £60, he commissioned an artist of modest fame, Thomas Holst, to provide a title-page illustration and a frontispiece showing the monster at the time of his laboratory birth. It is reasonable to assume that Mary Shelley saw and approved these plates.

Holst’s original title page shows Victor Frankenstein saying goodbye to his beloved Elizabeth as he sets off for Ingolstadt, where he is to study the sciences. Elizabeth Lavenza is the perfect young lady, ringletted and demure, with a crucifix strung over a chest as flat as a boy’s; Victor, in skirted tunic and an equally copious set of curls, looks away from her, his thoughts already fixed on the future.

The representation of Frankenstein’s laboratory at the moment that the monster wakes into life is more interesting. In later editions, it took the place of the title page. Atmospherically, the scene belongs to one of the gothic extravaganzas written by Percy Bysshe Shelley during his schooldays. The moon glares through an ancient window more appropriate to a Norman church than a student’s laboratory; magic runes hang on the wall; bones litter the floor. Straight haired and hollow-cheeked, the creature who stretches across the foreground of Holst’s arresting plate looks like Caliban on steroids. He has a gaunt beauty; you would never question the fact that he is human rather than the ‘daemon’ described by his maker, here seen taking a hasty departure from the birth chamber.

[caption id="attachment_3638" align="aligncenter" width="544"] T. P. Cooke in Presumption; or, The Fate of Frankenstein[/caption]

Images of how both Frankenstein and his creature might have looked have already been shaped by the novel’s remarkable success on stage. The miming skills of the actor T. P. Cooke were put to good use in 1823 when he first appeared as the creature in Richard Brinsley Peake’s genial adaptation, Presumption; or, The Fate of Frankenstein. Ladies, seeing the tall and well-proportioned Cooke lumbering out of the laboratory in search of his ‘father’, were alleged to have screamed and fainted, but this was only one of the ways in which the versatile Cooke interpreted his silent role. The penny text of the play which was widely available throughout the second half of the nineteenth century showed him posing on the edge of a table with a decidedly provocative smile, and with what looks like a twenties shift rucked up over his womanly thighs. Here, you can’t help feeling, was a source of inspiration both for Boris Karloff and for Tim Curry’s Frank N. Furter in the 1973 hit, The Rocky Horror Show.

Taking the play to France as Le Monstre et le magicien in 1826, Cooke showed his adaptability once more. There was no doubt about what the creature signified here, less than forty years after the Revolution; he was the spirit of the vengeful mob. Cooke’s creature, accordingly, became a creeping villain, his face distorted by hate, his matted locks hanging over hunched shoulders. The houses were packed.

[caption id="attachment_3640" align="aligncenter" width="596"]

T. P. Cooke in Presumption; or, The Fate of Frankenstein[/caption]

Images of how both Frankenstein and his creature might have looked have already been shaped by the novel’s remarkable success on stage. The miming skills of the actor T. P. Cooke were put to good use in 1823 when he first appeared as the creature in Richard Brinsley Peake’s genial adaptation, Presumption; or, The Fate of Frankenstein. Ladies, seeing the tall and well-proportioned Cooke lumbering out of the laboratory in search of his ‘father’, were alleged to have screamed and fainted, but this was only one of the ways in which the versatile Cooke interpreted his silent role. The penny text of the play which was widely available throughout the second half of the nineteenth century showed him posing on the edge of a table with a decidedly provocative smile, and with what looks like a twenties shift rucked up over his womanly thighs. Here, you can’t help feeling, was a source of inspiration both for Boris Karloff and for Tim Curry’s Frank N. Furter in the 1973 hit, The Rocky Horror Show.

Taking the play to France as Le Monstre et le magicien in 1826, Cooke showed his adaptability once more. There was no doubt about what the creature signified here, less than forty years after the Revolution; he was the spirit of the vengeful mob. Cooke’s creature, accordingly, became a creeping villain, his face distorted by hate, his matted locks hanging over hunched shoulders. The houses were packed.

[caption id="attachment_3640" align="aligncenter" width="596"] The Irish Frankenstein by John Tenniel[/caption]

A survey of the images derived from Frankenstein that have appeared since the 1831 Bentley edition shows that the creature’s present-day status as tabloid-speak for anything we mistrust or fear was achieved by nineteenth-century cartoonists working for the right-wing press. Thus, an 1833 drawing by James Parry presented the new Reform Bill as a hideously winged and taloned creature, a monstrous baby striding above ‘his political Frankenstein’s’, a scuttling crowd of tiny, frightened figures. One of John Tenniel’s satirical drawings for Punch showed a huge unshaven figure with the face of an ape and a dagger in his hand. The caption was ‘The Irish Frankenstein’. Another, ‘The Russian Frankenstein and His Monster’, depicted a terrified Cossack cowering beneath a monstrous construct of cannon barrels. A third, ‘The Brummagem Frankenstein’, showed a massive Midlands workman who had been stirred into life by John Bright, the reformer. Plump and fearful, Bright is shown scampering past the knees of his mammouth creation. This is the spirit in which the novel has continued to be interpreted by the popular press, as a warning against social progress.

Film-makers have, for the most part, been more sensitive in their response. (A striking exception was Thomas Edison’s 1910 Frankenstein, which, aiming at the general public, saw the creature as a splendid opportunity for horror effects.) William Pratt, better known as Boris Karloff, was offered the chance to replace Bela Lugosi in James Whale’s 1931 film. Bowed down by a shoulder brace, with his eyelids caked in putty and a forehead built up to improbable height by a tin panel, Karloff managed to convey a being both innocent and menacing, gentle and possessed of murderous strength. His reading of the part has superseded all others. Glenn Strange and Lon Chaney, both of whom played the creature, varied only slightly from the Karloff interpretation. Later versions, such as Kenneth Branagh’s well-intended but over-reverent film, have been careful to stress the pathos in the creature’s alienated state.

[caption id="attachment_3645" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

The Irish Frankenstein by John Tenniel[/caption]

A survey of the images derived from Frankenstein that have appeared since the 1831 Bentley edition shows that the creature’s present-day status as tabloid-speak for anything we mistrust or fear was achieved by nineteenth-century cartoonists working for the right-wing press. Thus, an 1833 drawing by James Parry presented the new Reform Bill as a hideously winged and taloned creature, a monstrous baby striding above ‘his political Frankenstein’s’, a scuttling crowd of tiny, frightened figures. One of John Tenniel’s satirical drawings for Punch showed a huge unshaven figure with the face of an ape and a dagger in his hand. The caption was ‘The Irish Frankenstein’. Another, ‘The Russian Frankenstein and His Monster’, depicted a terrified Cossack cowering beneath a monstrous construct of cannon barrels. A third, ‘The Brummagem Frankenstein’, showed a massive Midlands workman who had been stirred into life by John Bright, the reformer. Plump and fearful, Bright is shown scampering past the knees of his mammouth creation. This is the spirit in which the novel has continued to be interpreted by the popular press, as a warning against social progress.

Film-makers have, for the most part, been more sensitive in their response. (A striking exception was Thomas Edison’s 1910 Frankenstein, which, aiming at the general public, saw the creature as a splendid opportunity for horror effects.) William Pratt, better known as Boris Karloff, was offered the chance to replace Bela Lugosi in James Whale’s 1931 film. Bowed down by a shoulder brace, with his eyelids caked in putty and a forehead built up to improbable height by a tin panel, Karloff managed to convey a being both innocent and menacing, gentle and possessed of murderous strength. His reading of the part has superseded all others. Glenn Strange and Lon Chaney, both of whom played the creature, varied only slightly from the Karloff interpretation. Later versions, such as Kenneth Branagh’s well-intended but over-reverent film, have been careful to stress the pathos in the creature’s alienated state.

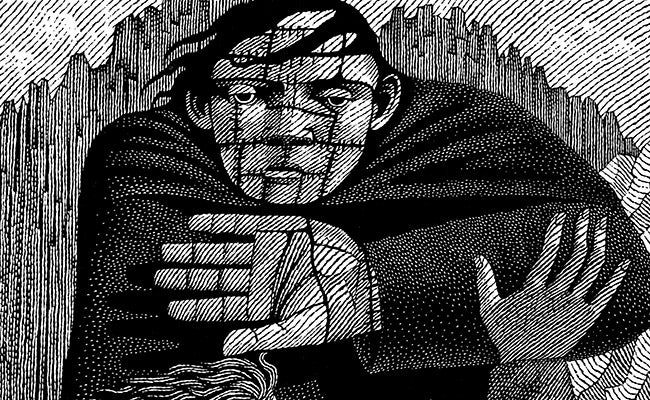

[caption id="attachment_3645" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Frankenstein illustrations © Harry Brockway[/caption]

For illustrators, while the temptation towards horrific effects has proved hard to resist, the subject has proved inspirational. Barry Moser, illustrating a lavish 1983 American edition, produced some of his most successful work when he stepped back from the characters and focused instead on the natural forces that play such a powerful part in the tale. By showing icebergs, a black skyline, a plot of budding flowers, a ship racing before the wind, he drew the reader’s attention to this important aspect of the story. Harry Brockway, who has produced the illustrations for The Folio Society’s edition, has chosen to focus on the creature, and rightly so, since its experiences are central to the author’s sense of her work as social propaganda. More than Moser, he has chosen to emphasise the moments of extreme emotion: the scene in which Frankenstein rejects his manufactured child; the desolation of the outcast, doomed to wander the world alone; the endeavours he makes to repay Frankenstein’s violence with reason; and, in the final set of illustrations, the descent into fury and revenge.

[caption id="attachment_3646" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Frankenstein illustrations © Harry Brockway[/caption]

For illustrators, while the temptation towards horrific effects has proved hard to resist, the subject has proved inspirational. Barry Moser, illustrating a lavish 1983 American edition, produced some of his most successful work when he stepped back from the characters and focused instead on the natural forces that play such a powerful part in the tale. By showing icebergs, a black skyline, a plot of budding flowers, a ship racing before the wind, he drew the reader’s attention to this important aspect of the story. Harry Brockway, who has produced the illustrations for The Folio Society’s edition, has chosen to focus on the creature, and rightly so, since its experiences are central to the author’s sense of her work as social propaganda. More than Moser, he has chosen to emphasise the moments of extreme emotion: the scene in which Frankenstein rejects his manufactured child; the desolation of the outcast, doomed to wander the world alone; the endeavours he makes to repay Frankenstein’s violence with reason; and, in the final set of illustrations, the descent into fury and revenge.

[caption id="attachment_3646" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Frankenstein illustrations © Harry Brockway[/caption]

One striking innovation has been made here; for the first time, it is suggested in a drawing that the creature does carry out his promise to immolate himself after Frankenstein’s own death. In the novel, there is no certainty that this oath will be fulfilled; here, his fiery ending is shown to take place. And, as with the enigmatic Karloff, there is no guessing whether the experience is one of relief, hope or despair. His eyes seem to search the sky for reassurance, but the text cannot tell us what answer he receives.

Frankenstein illustrations © Harry Brockway[/caption]

One striking innovation has been made here; for the first time, it is suggested in a drawing that the creature does carry out his promise to immolate himself after Frankenstein’s own death. In the novel, there is no certainty that this oath will be fulfilled; here, his fiery ending is shown to take place. And, as with the enigmatic Karloff, there is no guessing whether the experience is one of relief, hope or despair. His eyes seem to search the sky for reassurance, but the text cannot tell us what answer he receives.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2004 edition of the Folio Magazine. Frankenstein is available in a new Folio Collectable edition.

[caption id="attachment_3642" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Frankenstein's Monster: Boris Karloff; Glenn Strange; Lon Chaney[/caption]

The novel, brought out by the London firm of Lackington in 1818, was initially unillustrated. In 1831, when Richard Bentley acquired the copyright from Mary Shelley for £60, he commissioned an artist of modest fame, Thomas Holst, to provide a title-page illustration and a frontispiece showing the monster at the time of his laboratory birth. It is reasonable to assume that Mary Shelley saw and approved these plates.

Holst’s original title page shows Victor Frankenstein saying goodbye to his beloved Elizabeth as he sets off for Ingolstadt, where he is to study the sciences. Elizabeth Lavenza is the perfect young lady, ringletted and demure, with a crucifix strung over a chest as flat as a boy’s; Victor, in skirted tunic and an equally copious set of curls, looks away from her, his thoughts already fixed on the future.

The representation of Frankenstein’s laboratory at the moment that the monster wakes into life is more interesting. In later editions, it took the place of the title page. Atmospherically, the scene belongs to one of the gothic extravaganzas written by Percy Bysshe Shelley during his schooldays. The moon glares through an ancient window more appropriate to a Norman church than a student’s laboratory; magic runes hang on the wall; bones litter the floor. Straight haired and hollow-cheeked, the creature who stretches across the foreground of Holst’s arresting plate looks like Caliban on steroids. He has a gaunt beauty; you would never question the fact that he is human rather than the ‘daemon’ described by his maker, here seen taking a hasty departure from the birth chamber.

[caption id="attachment_3638" align="aligncenter" width="544"]

Frankenstein's Monster: Boris Karloff; Glenn Strange; Lon Chaney[/caption]

The novel, brought out by the London firm of Lackington in 1818, was initially unillustrated. In 1831, when Richard Bentley acquired the copyright from Mary Shelley for £60, he commissioned an artist of modest fame, Thomas Holst, to provide a title-page illustration and a frontispiece showing the monster at the time of his laboratory birth. It is reasonable to assume that Mary Shelley saw and approved these plates.

Holst’s original title page shows Victor Frankenstein saying goodbye to his beloved Elizabeth as he sets off for Ingolstadt, where he is to study the sciences. Elizabeth Lavenza is the perfect young lady, ringletted and demure, with a crucifix strung over a chest as flat as a boy’s; Victor, in skirted tunic and an equally copious set of curls, looks away from her, his thoughts already fixed on the future.

The representation of Frankenstein’s laboratory at the moment that the monster wakes into life is more interesting. In later editions, it took the place of the title page. Atmospherically, the scene belongs to one of the gothic extravaganzas written by Percy Bysshe Shelley during his schooldays. The moon glares through an ancient window more appropriate to a Norman church than a student’s laboratory; magic runes hang on the wall; bones litter the floor. Straight haired and hollow-cheeked, the creature who stretches across the foreground of Holst’s arresting plate looks like Caliban on steroids. He has a gaunt beauty; you would never question the fact that he is human rather than the ‘daemon’ described by his maker, here seen taking a hasty departure from the birth chamber.

[caption id="attachment_3638" align="aligncenter" width="544"] T. P. Cooke in Presumption; or, The Fate of Frankenstein[/caption]

Images of how both Frankenstein and his creature might have looked have already been shaped by the novel’s remarkable success on stage. The miming skills of the actor T. P. Cooke were put to good use in 1823 when he first appeared as the creature in Richard Brinsley Peake’s genial adaptation, Presumption; or, The Fate of Frankenstein. Ladies, seeing the tall and well-proportioned Cooke lumbering out of the laboratory in search of his ‘father’, were alleged to have screamed and fainted, but this was only one of the ways in which the versatile Cooke interpreted his silent role. The penny text of the play which was widely available throughout the second half of the nineteenth century showed him posing on the edge of a table with a decidedly provocative smile, and with what looks like a twenties shift rucked up over his womanly thighs. Here, you can’t help feeling, was a source of inspiration both for Boris Karloff and for Tim Curry’s Frank N. Furter in the 1973 hit, The Rocky Horror Show.

Taking the play to France as Le Monstre et le magicien in 1826, Cooke showed his adaptability once more. There was no doubt about what the creature signified here, less than forty years after the Revolution; he was the spirit of the vengeful mob. Cooke’s creature, accordingly, became a creeping villain, his face distorted by hate, his matted locks hanging over hunched shoulders. The houses were packed.

[caption id="attachment_3640" align="aligncenter" width="596"]

T. P. Cooke in Presumption; or, The Fate of Frankenstein[/caption]

Images of how both Frankenstein and his creature might have looked have already been shaped by the novel’s remarkable success on stage. The miming skills of the actor T. P. Cooke were put to good use in 1823 when he first appeared as the creature in Richard Brinsley Peake’s genial adaptation, Presumption; or, The Fate of Frankenstein. Ladies, seeing the tall and well-proportioned Cooke lumbering out of the laboratory in search of his ‘father’, were alleged to have screamed and fainted, but this was only one of the ways in which the versatile Cooke interpreted his silent role. The penny text of the play which was widely available throughout the second half of the nineteenth century showed him posing on the edge of a table with a decidedly provocative smile, and with what looks like a twenties shift rucked up over his womanly thighs. Here, you can’t help feeling, was a source of inspiration both for Boris Karloff and for Tim Curry’s Frank N. Furter in the 1973 hit, The Rocky Horror Show.

Taking the play to France as Le Monstre et le magicien in 1826, Cooke showed his adaptability once more. There was no doubt about what the creature signified here, less than forty years after the Revolution; he was the spirit of the vengeful mob. Cooke’s creature, accordingly, became a creeping villain, his face distorted by hate, his matted locks hanging over hunched shoulders. The houses were packed.

[caption id="attachment_3640" align="aligncenter" width="596"] The Irish Frankenstein by John Tenniel[/caption]

A survey of the images derived from Frankenstein that have appeared since the 1831 Bentley edition shows that the creature’s present-day status as tabloid-speak for anything we mistrust or fear was achieved by nineteenth-century cartoonists working for the right-wing press. Thus, an 1833 drawing by James Parry presented the new Reform Bill as a hideously winged and taloned creature, a monstrous baby striding above ‘his political Frankenstein’s’, a scuttling crowd of tiny, frightened figures. One of John Tenniel’s satirical drawings for Punch showed a huge unshaven figure with the face of an ape and a dagger in his hand. The caption was ‘The Irish Frankenstein’. Another, ‘The Russian Frankenstein and His Monster’, depicted a terrified Cossack cowering beneath a monstrous construct of cannon barrels. A third, ‘The Brummagem Frankenstein’, showed a massive Midlands workman who had been stirred into life by John Bright, the reformer. Plump and fearful, Bright is shown scampering past the knees of his mammouth creation. This is the spirit in which the novel has continued to be interpreted by the popular press, as a warning against social progress.

Film-makers have, for the most part, been more sensitive in their response. (A striking exception was Thomas Edison’s 1910 Frankenstein, which, aiming at the general public, saw the creature as a splendid opportunity for horror effects.) William Pratt, better known as Boris Karloff, was offered the chance to replace Bela Lugosi in James Whale’s 1931 film. Bowed down by a shoulder brace, with his eyelids caked in putty and a forehead built up to improbable height by a tin panel, Karloff managed to convey a being both innocent and menacing, gentle and possessed of murderous strength. His reading of the part has superseded all others. Glenn Strange and Lon Chaney, both of whom played the creature, varied only slightly from the Karloff interpretation. Later versions, such as Kenneth Branagh’s well-intended but over-reverent film, have been careful to stress the pathos in the creature’s alienated state.

[caption id="attachment_3645" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

The Irish Frankenstein by John Tenniel[/caption]

A survey of the images derived from Frankenstein that have appeared since the 1831 Bentley edition shows that the creature’s present-day status as tabloid-speak for anything we mistrust or fear was achieved by nineteenth-century cartoonists working for the right-wing press. Thus, an 1833 drawing by James Parry presented the new Reform Bill as a hideously winged and taloned creature, a monstrous baby striding above ‘his political Frankenstein’s’, a scuttling crowd of tiny, frightened figures. One of John Tenniel’s satirical drawings for Punch showed a huge unshaven figure with the face of an ape and a dagger in his hand. The caption was ‘The Irish Frankenstein’. Another, ‘The Russian Frankenstein and His Monster’, depicted a terrified Cossack cowering beneath a monstrous construct of cannon barrels. A third, ‘The Brummagem Frankenstein’, showed a massive Midlands workman who had been stirred into life by John Bright, the reformer. Plump and fearful, Bright is shown scampering past the knees of his mammouth creation. This is the spirit in which the novel has continued to be interpreted by the popular press, as a warning against social progress.

Film-makers have, for the most part, been more sensitive in their response. (A striking exception was Thomas Edison’s 1910 Frankenstein, which, aiming at the general public, saw the creature as a splendid opportunity for horror effects.) William Pratt, better known as Boris Karloff, was offered the chance to replace Bela Lugosi in James Whale’s 1931 film. Bowed down by a shoulder brace, with his eyelids caked in putty and a forehead built up to improbable height by a tin panel, Karloff managed to convey a being both innocent and menacing, gentle and possessed of murderous strength. His reading of the part has superseded all others. Glenn Strange and Lon Chaney, both of whom played the creature, varied only slightly from the Karloff interpretation. Later versions, such as Kenneth Branagh’s well-intended but over-reverent film, have been careful to stress the pathos in the creature’s alienated state.

[caption id="attachment_3645" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Frankenstein illustrations © Harry Brockway[/caption]

For illustrators, while the temptation towards horrific effects has proved hard to resist, the subject has proved inspirational. Barry Moser, illustrating a lavish 1983 American edition, produced some of his most successful work when he stepped back from the characters and focused instead on the natural forces that play such a powerful part in the tale. By showing icebergs, a black skyline, a plot of budding flowers, a ship racing before the wind, he drew the reader’s attention to this important aspect of the story. Harry Brockway, who has produced the illustrations for The Folio Society’s edition, has chosen to focus on the creature, and rightly so, since its experiences are central to the author’s sense of her work as social propaganda. More than Moser, he has chosen to emphasise the moments of extreme emotion: the scene in which Frankenstein rejects his manufactured child; the desolation of the outcast, doomed to wander the world alone; the endeavours he makes to repay Frankenstein’s violence with reason; and, in the final set of illustrations, the descent into fury and revenge.

[caption id="attachment_3646" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Frankenstein illustrations © Harry Brockway[/caption]

For illustrators, while the temptation towards horrific effects has proved hard to resist, the subject has proved inspirational. Barry Moser, illustrating a lavish 1983 American edition, produced some of his most successful work when he stepped back from the characters and focused instead on the natural forces that play such a powerful part in the tale. By showing icebergs, a black skyline, a plot of budding flowers, a ship racing before the wind, he drew the reader’s attention to this important aspect of the story. Harry Brockway, who has produced the illustrations for The Folio Society’s edition, has chosen to focus on the creature, and rightly so, since its experiences are central to the author’s sense of her work as social propaganda. More than Moser, he has chosen to emphasise the moments of extreme emotion: the scene in which Frankenstein rejects his manufactured child; the desolation of the outcast, doomed to wander the world alone; the endeavours he makes to repay Frankenstein’s violence with reason; and, in the final set of illustrations, the descent into fury and revenge.

[caption id="attachment_3646" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Frankenstein illustrations © Harry Brockway[/caption]

One striking innovation has been made here; for the first time, it is suggested in a drawing that the creature does carry out his promise to immolate himself after Frankenstein’s own death. In the novel, there is no certainty that this oath will be fulfilled; here, his fiery ending is shown to take place. And, as with the enigmatic Karloff, there is no guessing whether the experience is one of relief, hope or despair. His eyes seem to search the sky for reassurance, but the text cannot tell us what answer he receives.

Frankenstein illustrations © Harry Brockway[/caption]

One striking innovation has been made here; for the first time, it is suggested in a drawing that the creature does carry out his promise to immolate himself after Frankenstein’s own death. In the novel, there is no certainty that this oath will be fulfilled; here, his fiery ending is shown to take place. And, as with the enigmatic Karloff, there is no guessing whether the experience is one of relief, hope or despair. His eyes seem to search the sky for reassurance, but the text cannot tell us what answer he receives.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2004 edition of the Folio Magazine. Frankenstein is available in a new Folio Collectable edition.