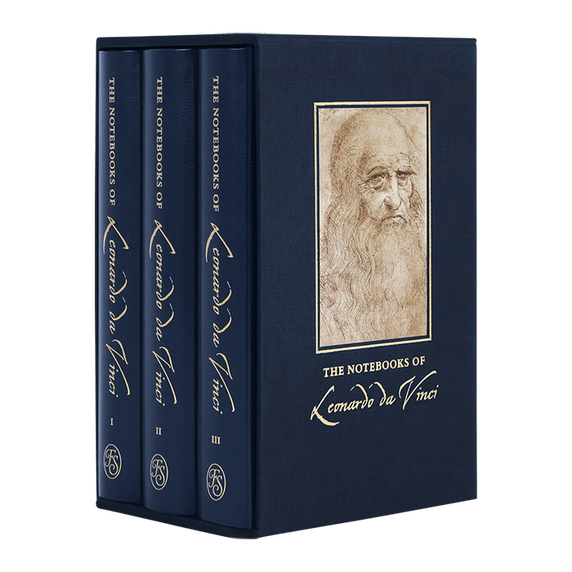

Commemorating the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci, this magnificent Folio collector’s edition reveals his brilliance in three beautifully illustrated volumes with stunning gold-blocked bindings.

Translated by Professor M. A. Screech

Selected and introduced by Sarah Bakewell

The Folio Society presents an exquisite gold-and-leather hardback of Essays by Renaissance nobleman and thinker Michel de Montaigne.

‘Montaigne straddles the old and the new worlds … His aperçus and obiter dicta have the power to delight still; his honesty with himself, his resistance to self-congratulation, is timeless, and precious’

- Guardian

How to get on with people, how to deal with violence, how to bring up children, how to live? These questions obsessed Renaissance nobleman and philosopher Michel de Montaigne, whose free-roaming explorations of his own thoughts and experiences were unlike anything written before. Wise but questioning, witty and idiosyncratic, and incredibly modern in outlook, Montaigne’s thoughts are still relatable 400 years after his death. And now Folio has produced a fitting tribute with an edition, beautifully adorned in gold and leather, featuring an exclusive selection of his best essays – chosen by acclaimed Montaigne biographer Sarah Bakewell – showing the vast variety and originality of his work, from short, quirky pieces to longer investigations of sex, writing and friendship. Bakewell has also provided a comprehensive and insightful introduction on the man, his life, his work and his everlasting influence.

Quarter-bound in blocked leather with blocked cloth sides

Set in Arno Pro with Dawnora Initials

440 pages

Black & white frontispiece

Printed in two colours throughout

Ribbon marker

Printed endpapers

Gilded page edges

Cloth slipcase

11˝ x 6¾˝

Michel de Montaigne, often called ‘the first modern man’, was one of the most influential figures of the Renaissance, singlehandedly responsible for popularising the essay as a literary form. In 1571, Montaigne retired from ‘the slavery of the court and of public duties’ to his estates in order to devote himself to reflection, reading and writing. The result was 20 years of observations distilled into what he called ‘essais’, and an instant bestseller.

What had Montaigne produced that struck such a chord, not just with the French public but also his contemporaries abroad, including Shakespeare, Descartes and Pascal? The answer is in his questions: What is it to be a human being? Why do other people behave as they do? Why do I behave as I do? Why do animals behave as they do? He considered his feelings; how it felt to be angry or excited, grumpy or lustful. He sought to understand the problem with memory – that one could have a brilliant idea and then forget it immediately – he looked for answers on how to love, or how to manage one’s boring responsbilities. Sarah Bakewell aptly describes him as ‘a brilliant psychologist, but also a moral philosopher in the fullest sense of the word. He did not tell us what we should do, but explored what we actually do.’ And his appeal continues centuries later because we are all still concerned with the one question Montaigne sought to answer: how does one live?

Sarah Bakewell is a renowned historical biographer and the author of How to Live: A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer (2010). For this Folio edition she has selected essays that represent the huge variety and originality of Montaigne’s work, from short, quirky pieces to longer investigations on sex, writing, friendship and education. In this exclusive collection you will find ‘On Fear’, ‘On the custom of wearing clothing’ and ‘On Books’, as well as profound statements on ‘How our mind tangles itself up’ and ‘How the soul discharges its emotions against false objects when lacking real ones’. There is humour, contradiction and a humble acceptance of man’s lack of knowledge.

Michel Eyquem de Montaigne: sixteenth-century seigneur, sometime magistrate and mayor of Bordeaux, early retirer, and the creator of the genre for which he also created the word: essay

In addition, Bakewell’s detailed introduction provides the historical and biographical context behind the man who would become a defining influence on literature in the century that followed. She elaborates on the continued interpretations of his work – ‘He is so motley and inconsistent that he lends himself to almost any interpretation, and each generation has hand-picked a Montaigne to fit their own image, making him in turn a wise Stoic, a challenging Sceptic, a proto-Enlightenment freethinker, an amiable companion for the Victorian reader’s fireside (so long as one ignores the sexy bits), and a subversive twentieth-century postmodernist’ – and discusses the many imitators that followed him, even today ‘in the blogways of the internet’.

Michel Eyquem de Montaigne (1533–92) was one of the most important figures in the late French Renaissance, known both for his literary innovations and for his contributions to philosophy. As a writer, he is credited with having developed a new form of literary expression, the essay, a brief and admittedly incomplete treatment of a topic germane to human life that blends philosophical insights with historical anecdotes and autobiographical details, all presented from the author’s own personal perspective. As a philosopher, he is best known for his scepticism, which profoundly influenced major figures in the history of philosophy such as Descartes and Pascal.

Montaigne was born the son of a nobleman at the Château Montaigne, near Bordeaux. In 1557 he began a career as a magistrate, first in a regional court and later in the Bordeaux Parlement, one of the eight parlements that together comprised the highest court of justice in France. There he encountered Etienne de La Boétie, with whom he formed an intense friendship that lasted until La Boétie’s sudden death in 1563. Years later, the bond he shared with La Boétie would inspire one of Montaigne’s best-known essays, ‘Of Friendship’ (‘On Affectionate Relationships’). Two years after La Boétie’s death Montaigne married Françoise de la Chassaigne. In 1570 Montaigne sold his office in the Parlement and retreated to his château, where a year later he dedicated himself to the management of the château.

Soon after he began to write, and in 1580 he published the first two books of his Essays. Retirement did not mean isolation, however. Montaigne became involved in the turbulent religious politics of 16th-century France and, as a moderate Catholic, worked hard to keep the peace – as mayor of Bordeaux in 1581 and as a diplomatic link between opposing forces. He loathed the fanaticism and cruelties of the religious wars, but sided with Catholic orthodoxy and legitimate monarchy. He died at Montaigne in 1592 while preparing the final, and richest, edition of his Essays.

M. A. Screech (1926–2018) was a Renaissance scholar of international renown. He was a Fellow of Wolfson College, Oxford, of All Souls College, Oxford, and of University College London. He was editor and translator of Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel (2006), as well as of the Complete Essays of Montaigne (1981), for which he was promoted Chevalier dans l’Ordre du Mérite in 1982. His other works include Rabelais, Montaigne and Melancholy (1983), Erasmus: Ecstasy and the Praise of Folly (1988) and Laughter at the Foot of the Cross (1997). Screech was ordained, in Oxford, a deacon in 1994 and a priest in 1995.

Sarah Bakewell is a historical biographer and writer on the history of ideas. Her biography of Montaigne, How to Live: A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer (2010), won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Biography in the US and the Duff Cooper Prize for Non-Fiction in the UK, and was shortlisted for the Costa Biography Award and the Marsh Biography Award. Her other books include The Smart (2001), The English Dane (2005) and At the Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails (2016), which was shortlisted for the PEN Hessell-Tiltman Prize, and was one of the New York Times Top Ten Books of the Year.